This was originally posted on reddit a while back, and I’ve been meaning to post it here.

The what

I wrote 52 short stories across 9 different genres that totaled over 52,000 words. My constraints were one short story every Sunday, at least 500 words, and I’d publish them on my personal website. I’d consider them as first drafts, some needing more work than others, some exist as scenes, and some serve as the start of a longer story. I gave myself the challenge in order “just write,†but also explore different characters, genres and ideas.

Success and learnings

In doing this, I now have a body of work, where I could (and will) return to and edit them to be excellent stories. And with this body of work, I can see what tics or habits I lean on. For example, I need to get better at showing emotion in a variety of ways, and my ingrained aversion to to-be verbs causes verb tense issues at times. Moreover, if I don’t have a clear vision of an ending, my endings get muddy and flat no matter what idea I had at the start.

In exploring ideas, I found fun in writing other genres and challenge in working to incorporate people different than my male, American, hetero self. The western I wrote about a bar tender recounting a story of a samurai in his saloon was one of the best, and I realized I could work with the conventions of the genre and still be able to execute; the same can be said of the fantasy stories I played with. And I made conscious decisions to write women, minorities, LGBT, in fantastic or mundane scenarios as normal, ordinary people. Did I do them justice? I don’t know. I’ll need to get feedback, especially for the story where a transwoman goes and buys a gun in reaction to an election.

Story telling may just be an exercise in empathy.

Ideas

Ideas came from all over:

- A picture of greenhouse I saw on r/pics spurned a horror yarn with two teenage boys

- News headlines gave me more than one

- My father asking about whether I wanted any of our Brio trains chugged along into a magical realist story

- A joking comment about bourbon poured into oatmeal swirled into a story about a cam girl

- Self driving cars can go on dark rides along technology’s cliff

- Storage unit + science = !

- Ferris wheel that goes underground

- Social media is ripe for exploration

And on and on…

I even managed to write three on my phone while traveling 35,000 feet up in the air. But I’ll be honest, there were days where I scraped my keyboard for words. One idea I’ve had for sometime revolves around the woman in white ghost story trope but at a whiskey distillery. I was miserable writing it—i wasn’t feeling well, the setup was off, and it needed to be at least 5,000-6,000 words to create the tension. It was my worst. I cheated with the end, writing, “everything burned, and he died.â€

I do intend to go back to that one and redo it.

Misc

- Scrivener served as my main tool; the iOS Notes app, and then the iOS Scrivener app for mobile

- I listened to a lot of post rock, jazz, and ambient music while writing

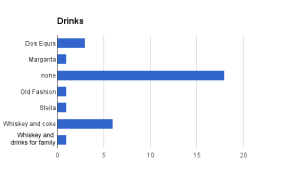

- I drank coffee, water, Mountain Dew, beer, or whiskey

- I really need to get dictation set up. I played with Dragon and a headset, but got frustrated with it

Stats

- Total words: 52258

- Average: 1005

- Median: 885

- Longest: 2351

- Shortest: 515

Genre breakdown

| Genre | Count |

|---|---|

| Contemporary | 15 |

| Crime | 2 |

| Fantasy | 7 |

| Historical Fiction | 1 |

| Horror | 6 |

| Literary | 1 |

| Sci-fi | 15 |

| Supernatural | 2 |

| Western | 2 |

| Young Adult | 1 |